On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy struck New York City. At the time, Manhattan had the largest collection of sustainably-designed buildings in the United States but still incurred $19 billion in storm-related damage. The juxtaposition of this poses the question, “How sustainable is a building that is not designed to be resilient?” Even the most sustainably-designed building is harmful to the environment and a waste of resources if it has to undergo a major renovation or be demolished shortly after it is built.

Over the last decade, sustainable (“green”) design principles have received significant media coverage and many states have mandated that buildings built with state funds be designed to meet minimum sustainable design standards. Currently, the most popular certification system is the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification that is administered by the United States Green Building Council (USGBC). To date, 13.8 billion square feet of space worldwide has achieved LEED certification. The LEED certification system has evolved since it was first released to encourage a more systematic approach towards achieving sustainability; however, it still does not do enough to encourage resilient design. If anything, some of the complicated mechanical and fenestration systems that LEED encourages are likely less resilient than simpler ones.

While most developers are familiar with sustainable design practices and LEED, few are familiar with resilient design standards – and those that are would have a difficult time defining exactly what it is. The Resilient Design Institute defines resiliency as the capacity to adapt to changing conditions and to maintain or regain functionality and vitality in the face of stress or disturbance. Most developers would assume that a building designed to meet the building code has some inherent resilience, but often natural events occur that impose forces on buildings that the building code did not anticipate. Also, resilient buildings need to be able to adapt to the changing economic climate in which they are located – it has only been possible to convert existing warehouses and factories to lofts because they were originally designed with a level or robustness that is not necessarily inherent in today’s buildings.

The list below expands on some of these events, but is not complete by any means.

Rising Sea Levels – At a minimum, world sea levels are expected to increase by a minimum of three feet globally over the next thirty years. Elizabeth Kolbert’s article, “Miami is Flooding” published in the December 21st issue of The New Yorker details how this will impact south Florida in the coming years.

Extreme Weather Events – In addition to rising sea levels, the number of extreme weather events has increased over the last fifty-years and is likely to continue to increase as the effects of climate change become more pronounced. Future events may include prolonged heat waves, larger hurricanes, and more intense downpours.

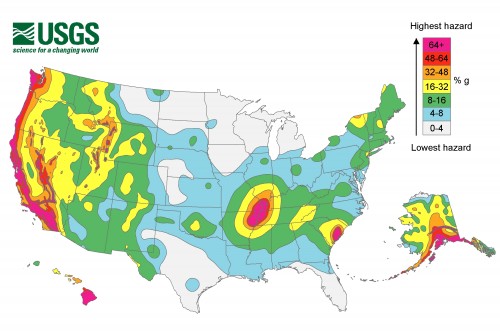

Earthquakes – Everyone is aware that earthquakes are a major threat to California and most of the buildings there have been built or retrofitted to resist their effects; however, there are also major fault lines in Missouri, Illinois, and South Carolina that are much less understood and buildings in these areas are typically not built to withstand earthquakes.

Terrorist Attacks – While it’s impossible to predict the next terrorist attack or what the nature of it will be, it’s almost certain, that, unfortunately, buildings will continue to be a target. Buildings could be made more resilient to this threat by incorporating mechanical systems that are less dependent on the public grid and hardened architectural features.

Economic Cycles – The economy in all cities evolve as one industry gives way to another. For example, in the 1940s and 50s, Boston’s economy was highly dependent on manufacturing, but as those industrial jobs left, the city’s economy has become heavily dependent on bio-tech and finance. To remain viable, buildings need to be designed so that they can be adapted to serve multiple purposes and tenant densities during their lifetimes.

Disruptive Technologies – Automated vehicles and 3-D printing are two technologies that are currently receiving a lot of media coverage. Who knows if these technologies will end up being truly “disruptive”; however, a building that is unable to change to facilitate the impacts of these and similar technologies is not resilient.

While it might seem like there are too many considerations to design for, most of them can be addressed by designing and erecting buildings that are robust, well located, and adaptable. For instance, in flood zones, instead of designing buildings for a 100-year flooding event, design for the 500-year flood. Instead of designing a building with minimum floor-to-floor heights and eccentric floor plates, use a floor-to-floor height that is a foot taller than the minimum and a more traditional floor plate layout.

It is much easier and affordable to build this robustness and flexibility into buildings at inception than it is after they are built. To incentivize building sustainable, resilient buildings, rating systems such as LEED should reward developers for taking resiliency into consideration; otherwise, it will be impossible to realize the benefits that sustainable buildings offer.