In Part I, we discussed Jonathan Litt’s battle with Taubman Centers. In Part II, we will take a look at the underlying trends that led to this, and the broader state of the retail real estate sector. Finally, in Part III will examine how the performance of retail real estate is measured, and how some analysts are proposing new metrics to reflect current trends in the sector.

Activist investor Jonathan Litt’s battle to create value at Taubman Centers (NYSE: TCO) is not surprising, given the current dynamics of the Shopping Mall REIT sector. As most investors know, the retail sector is broadly under pressure from factors ranging from e-commerce/internet sales to changing consumer tastes and shifting demographics. There is a growing divide between the performance of “Class A” and Class “B” and “C,” malls, and this gulf has continued to grow wider with the downsizing of some of the most iconic retailers of the 20th century.

Briefly, retail real estate is the result of one of the most basic functions of human society and of an economy: the free exchange of goods. Retail real estate fills the need for space where consumers physically travel to exchange goods. This is rooted to ancient times, from the bazaars of the ancient world to the fairs of Medieval England. Cities in Ancient Mesopotamia and Persia were founded as the result of marketplaces springing up along trade routes, such as present-day Baghdad, Cairo and Tehran. After World War II, the outsized, modern American version of this, the shopping center, began to spring up in suburban areas, succeeding the “main street USA” strips of retail and urban shopping districts of the preceding 100 years. While certain urban retail districts such at New York’s 5th Avenue stood the test of time, the combination of population shift to the suburbs, the emerging automobile culture, and the unprecedented prosperity of postwar America led to the emergence of the shopping mall.

The concept of a shopping centers with hundreds of stores under one roof, anchored by large department stores, is a concept that is barely two generations old. The phenomenon of hundreds of independent retails permanently locating in one place has been in place globally for centuries, from the massive street markets of the Far East to the Victorian Arcades of 19th century England. However, the model of a massive enclosed shopping center designed with the automobile in mind was conceived and evolved as more or less a collaboration between large retailers and private developers. The first few examples opened in 1954-56 and included the noted partnership between Macy’s and William Zeckendorf that produced Roosevelt Field Mall in East Garden City, Long Island (See Above: Aerial Photo of Roosevelt Field Mall, 1959). In the 1960s, developers such as Melvin Simon, Alfred Taubman, and Edward DeBartolo Sr. shifted their focus exclusively to mall development. As the names suggest, some of these developers of yesteryear evolved into the shopping mall REITs of present day, with many going public in the early 1990s, Taubman (NYSE: TCO) doing so in 1992 and Simon in 1993 (NYSE: SPG). Despite the difficult environment for shopping malls, Simon Property Group remains the largest REIT by market capitalization.

The concept of a shopping centers with hundreds of stores under one roof, anchored by large department stores, is a concept that is barely two generations old. The phenomenon of hundreds of independent retails permanently locating in one place has been in place globally for centuries, from the massive street markets of the Far East to the Victorian Arcades of 19th century England. However, the model of a massive enclosed shopping center designed with the automobile in mind was conceived and evolved as more or less a collaboration between large retailers and private developers. The first few examples opened in 1954-56 and included the noted partnership between Macy’s and William Zeckendorf that produced Roosevelt Field Mall in East Garden City, Long Island (See Above: Aerial Photo of Roosevelt Field Mall, 1959). In the 1960s, developers such as Melvin Simon, Alfred Taubman, and Edward DeBartolo Sr. shifted their focus exclusively to mall development. As the names suggest, some of these developers of yesteryear evolved into the shopping mall REITs of present day, with many going public in the early 1990s, Taubman (NYSE: TCO) doing so in 1992 and Simon in 1993 (NYSE: SPG). Despite the difficult environment for shopping malls, Simon Property Group remains the largest REIT by market capitalization.

Fast forward to 2017. Nearly all of those in real estate and much of the American public are well aware of the challenges that the typical shopping mall faces. 2017 began right off the bat with gloomy news for the sector. Within hours of each other on January 4, historic US retailing stalwarts Macy’s and Sears both announced large-scale store closures. Specifically, Sears Holdings announced the closing of 108 Kmart and 42 Sears locations over the next few months. Sears also announced the sale of its Craftsman brand, a move that increased speculation that Sears may be nearing bankruptcy. In addition, Macy’s announced the closing of 68 locations as part of a previously announced plan to close 100 stores, with the remaining 32 to close over the next three years as leases or operating covenants expire.

The retail industry will pay close attention to just which Sears and Macy’s will ultimately be shuttered, as such closings have inevitable ripple effects on the shopping centers which they anchor, many of which are Class B and Class C malls that are already struggling. Losing such anchor tenants has often been a prelude to the closing of such malls altogether, and retail analysts expect this trend to continue. Morgan Stanley noted on January 5 that of the 578 malls that have Sears as a tenant (approximately 53% of all shopping centers in the “Mall” category), 350 of them (61%) have Macy’s as a tenant as well.

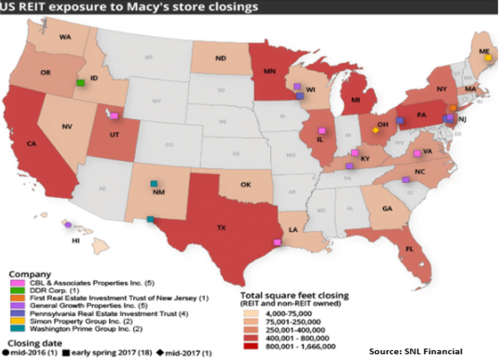

The impact on REITs will be wide-ranging, affecting those which are considered healthy, to those which are already experiencing difficulties (see map of closures below). Anticipating these trends nearly two decades ago, firms such as Simon Property Group have in recent years spun off the lower-performing assets in their portfolio into separate REITs. However, even such prudent moves have not completely shielded them from the latest round of retail closings.

Most, if not all “Class A” malls continue to perform well via traditional metrics in the current market environment. Bloomfield Hills, Michigan-based Taubman Centers owns the most productive mall portfolio in the U.S., many of which it developed from the 1960s through the 1990s. As would be expected with a productive asset, Class A malls are very rarely transacted on a large scale. With this in mind, it should not be surprising that Taubman has been the target of activist investors such as Jonathan Litt, and competitors such as Simon Property Group. In 2003, Simon attempted a hostile takeover of Taubman, which would have enabled it to pick up a number of Class A assets in one fell swoop. Class “B” and “C” malls are, for the most part, not attractive assets to institutional investors such as large Shopping Mall REITs, and consumer preferences have shifted away from regional shopping malls.

Anticipating this, Simon shifted its focus to higher-end malls throughout the 2000s via acquisition of firms such as Rodamco and other smaller shopping mall owners. In the latter case, SPG often sought to acquire a few select assets, after which it would divest the remainder of the acquired portfolio. Much of this was accomplished in 2013-15, when SPG spun off many of its lower-end assets into Washington Prime Group, which later acquired Glimcher Realty Trust and is currently known as W.P. Glimcher. Such moves, in addition to its robust development of outlet malls, have left SPG better able to handle the retail environment of 2017, as evidenced by its strong Q4 2016 earnings, ($2.91/share, beating analyst expectations by $.34, or 13%).

As the the shopping mall sector continues to move forward into the brave new world of retail, analysts have begun to re-examine how the performance of retail centers will be measured going forward, a process which involves revisiting the role of retail real estate itself, and how it is evolving in the 21st century. Amidst the shifting of sales from brick and mortar to online retail, it is clear that many of the historic metrics of mall performance may no longer be effective benchmarks, as only a subsector of malls is truly performing well. These questions and similar issues will be explored in Part III.