The importance of rivers is pervasive in urban history. Rivers initially provided humans with a source of food (fish) and fresh water, but most importantly allowed for agriculture which provided for the growth of substantial urban populations. In the United States, the major growth of cities took place during a global period of rapid industrialization, and the major American riverways were developed to promote both commerce and industrial development. Key sites along these rivers (typically at the source or mouth) have become some of the nation’s largest cities: New York City at the mouth of the Hudson River, New Orleans at the mouth of the Mississippi River, and Chicago at the western terminus of the Great Lakes chain that ultimately flows to the Atlantic Ocean through the St. Lawrence River.

Given the time period in which key American riverfronts were developed, it is no surprise that the physical riverfront largely took on an industrial nature. River current provided an early power source for American factories and mills, as well as a transportation method to move the textiles and other goods that were moved produced. Over time, these industrialized riverfront districts gave way to major industrial manufacturing districts. Along with this came significant river pollution, perhaps most apparent in the 13 fires that have engulfed the Cuyahoga River between 1868 and 1969.

With the slow regression of American factories and manufacturing, many U.S. cities have attempted to re-embrace the riverfront for its aesthetic attributes to improve the quality of life for its residents. While there are examples of this in many cities across the country, let’s take a look at what the nation’s three largest cities are doing.

New York City: The Brooklyn and Queens Riverfront

Like with many aspects of real estate, New York has led the way in redeveloping its riverfront. Manhattan has been effectively 100% built-out for decades and also has riverfront highways that reduce the ability to substantially alter the riverfront, which has pushed much of the new riverfront development across the East River to Brooklyn and Queens. In recent years, new innovative tech campuses have transformed these areas, as the Cornell Tech campus on Roosevelt Island has pushed new development across the East River to the Queens riverfront and the NYU in Brooklyn initiative have facilitated continued growth in the “Brooklyn Tech Triangle”.

The DUMBO riverfront was one of the earliest neighborhoods to receive a complete overhaul. David Walentas of Two Trees was the catalyst for this redevelopment, effectively buying the entire industrial neighborhood in the 1970s for $12 million and transforming it into the highest price residential and office submarket in the borough today. Further to the north, many are now familiar with the transformation of Williamsburg from an industrial district into one of the trendiest neighborhoods in New York with a significant artist community.

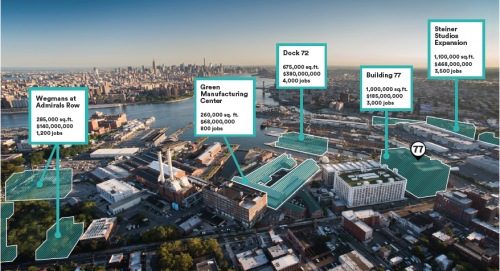

Connecting DUMBO and Williamsburg is the Brooklyn Navy Yard. While many point to the Dodgers baseball team moving from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in the 1950s as the beginning of a downward spiral for the borough, the real stimulant was the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s closure in 1966 after employing over 70,000 workers during World War II. Under Mayor Koch, the city formed the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation in 1981 to preserve quality industrial jobs and promote economic development and innovation within the Navy Yard. Over the past decade, the Navy Yard has become a hot spot for innovative and creative development activity, with over $700 million in new development currently underway. Projects include restoration and repurposing of several existing buildings as well as the new construction of Dock 72, which is being co-developed by Boston Properties and Rudin Management and will total 675,000 square feet of new office space that will be anchored by WeWork. The Navy Yard is also adding a retail center that will include Brooklyn’s first Wegmans grocery store as well as the repurposing of 126,000 square feet of industrial buildings for retail space. New residential development continues to sprout around the Navy Yard, including the $146 million Navy Green project which was completed in 2015.

Further north, the waterfront of Long Island City has seen tremendous development activity since the rezoning of 37 blocks along the riverfront in 2001. Since that time, over 10,000 new residential units and 1.5 million square feet of commercial space have been developed, including megaprojects such as Hunters Point South and Gotham Center. Long Island City’s development seeks to take advantage of the construction of the Cornell Tech campus on adjacent Roosevelt Island (opened 2017), but critics argue that LIC has failed to create a community feel that can be found in other parts of the city. Part of the solution to this is the promotion of the riverfront through infrastructure and park development.

Not only do these projects reimagine the urban fabric of Brooklyn and Queens, but they have also become a key marketing tool for the city in attempting to lure Amazon’s HQ2. While Long Island City offers substantial new development opportunities effectively adjacent to Cornell Tech, Brooklyn’s proposal to Amazon suggested diversification of office locations including larger-scale campus-like office space at the Brooklyn Navy Yard with possible expansion into Downtown Brooklyn or South Williamsburg. Not only do these proposals provide Amazon access to the intellectual capital of two technology-based university campuses, but they also allow Amazon to have a community impact that they seek in their RFP.

Chicago: 760 Acres of Opportunity

Similar to the rezoning of Long Island City in New York, Chicago passed the rezoning of the 760-acre North Branch Industrial Corridor along the North Branch of the Chicago River in July 2017 in an effort to transform the once vibrant industrial corridor into a mixed-use residential and business center environment. Specifically, the plan removed several Planned Manufacturing Districts and replaced them with flexible zoning districts to promote developer creativity. Large-scale development plans have already been unveiled in this corridor, including the Chicago Tribune site referred to as Freedom Center as well as preliminary plans for the Finkl Steel site. Both projects include significant investments in the riverfront, including public parks and bike trails.

Plans for development within the corridor will continue to evolve over a period of decades, but the impact on the city cannot be understated. The Freedom Center plans include up to 5,900 new units on approximately 30 developable acres, and while the Finkl Steel plans do not specify land uses, the 28-acre site is envisioned to encompass high density, mixed-use development that could include a similar number of residential units to the Freedom Center. Preliminary estimates for the Finkl Steel site, dubbed “Lincoln Yards,” include up to $10 billion in development costs.

Plans for development within the corridor will continue to evolve over a period of decades, but the impact on the city cannot be understated. The Freedom Center plans include up to 5,900 new units on approximately 30 developable acres, and while the Finkl Steel plans do not specify land uses, the 28-acre site is envisioned to encompass high density, mixed-use development that could include a similar number of residential units to the Freedom Center. Preliminary estimates for the Finkl Steel site, dubbed “Lincoln Yards,” include up to $10 billion in development costs.

In the South Loop, Related Midwest is also proposed dramatic riverfront development at the corner of Clark and Roosevelt. Dubbed “The 78” as the planned creation of the city’s 78th community area, the 62-acre site recently announced its first use: The Discovery Partners Institute. A partnership led by the University of Illinois in conjunction with the University of Chicago and Northwestern University, the public-private partnership will form a major education, research, and innovation hub for the city in the evolving South Loop. All three of these riverfront sites (Freedom Center, Lincoln Yards, and The 78) have been identified as potential locations for an Amazon HQ2.

Los Angeles: Acquisition of the “Crown Jewel” in LA River Revitalization Strategy

In the City of Angels, waterfront is most commonly associated with the city’s stretch of sandy beaches filled with surfers. But the city government has eyed an 11-mile stretch of the Los Angeles River for redevelopment for decades. In January 2017, the city acquired what it has referred to as the “crown jewel” of its riverfront revitalization plan: a 41-acre parcel previously used as a rail yard that is expected to cost $252 million to acquire, remediate, and add public improvements. Known as G2, the parcel is the first major piece of what is expected to be a $1.6 billion revitalization project and will open up one mile of riverfront for parks, hiking trails, and wildlife viewing. The entire project would restore a natural river (currently concrete) between Griffith Park in the Hollywood Hills to Downtown Los Angeles.

The 11-mile stretch of riverfront is easy to identify, but the funding mechanisms for the city’s vision and the plans for the site upon acquisition are as muddy as the river’s water. The California State Senate identified $25 million in state funds for the site in 2015, and the city expects over $25 million in federal funds for the site. But major questions remain over where the remainder of funding will come from, with some estimates that the city will need to pay for over 75% of the project.

The lack of funding also raises questions about the city’s long-term intentions for the site. One proposal was for the construction of an Olympic Village for the 2028 Summer Olympics, but this plan was scrapped in 2016. What does appear clear is that the city intends to use the riverfront to connect neighborhoods in the city. What is less apparent is how the city will acquire an incentivize development along what will never be the city’s most desirable waterfront.

———————————————————————————————–

Across America’s major cities, industrial riverfront districts are being targeted for future development and the accommodation of the growth of urban cores. Residents of these cities are already beginning to benefit from these efforts, with new parks, trails, and waterfront access already available. Developers are also seeing major opportunities in these areas, with many developers already reaping the benefits in cities like New York while others are ramping up new plans in Chicago and Los Angeles. The amenity of the riverfront has also been pitched to Amazon in multiple cities as it seeks a location for its HQ2.

Riverfront revitalization efforts are not specific to the three largest cities in the nation, as illustrated by a recent report by the Urban Land Institute. How is your city utilizing its riverfronts, and what opportunities do you see for future growth?