Real estate development occurring in the public domain often must grapple with the complicated perspectives of a variety of stakeholders. Practitioners must therefore be adept at addressing divergent values and priorities prudently and delivering results while simultaneously managing expectations. This article will examine one such recent scenario in the capital city of India. Indeed, over the last few months, the citizenry of Delhi has vehemently protested the proposed felling of 16,500 trees to enable the redevelopment of government officer housing in the southern part of the city (Times News Network, 2018). While the objections have led to a temporary stay on the felling, one must consider other concerns within the context of the project to balance competing objectives and look to strike a middle path. This article will examine this issue specifically through the lens of a) land as a resource, b) the need for affordable housing, and c) possible alternatives to a NIMBY-like attitude of maintaining green-leafed suburban development in the heart of a megapolis.

Government agencies are typically among the largest landholders in any country and India is no exception. It was only as recently as 2017 that the general public and many government agencies realized the scale of government land ownership in India after a Government Land Information System (GLIS) inventory project was put in place by the Prime Minister’s Office to record area, geo-positioning, and ownership rights (Das Gupta, 2017). Even without all the data being collated, and with a significant portion of the data classified by the Ministry of Defence (MoD), the total federal government landownership amounted to 5,215 square miles (i.e., about nine times the size of Delhi). With a large part of this land being urban – cantonments[1], low density government housing, and railway land (coincidentally the largest land holder after the MoD), an artificial scarcity of a precious public resource is created in burgeoning cities.

While there has been no estimate of the amount of land required to bridge the deficit of the 18 million homes required across the country, an ANB Capital Advisors 2018 report estimating a need for $330 billion for construction funding (Mishra, 2018) gives some sense of scale. Instead of leveraging development within the formal process, poor land management has led to a “wicked”[2] problem of encroachments and squatter settlements that informally bridge the gap of the unmet housing needs within a rapidly urbanizing population. Cities in India maintain a sustainable density only because of these informal settlements, while the formal planning process, especially of government land, continues to not consume land to its full potential.

Even after calls from within the government to monetize unutilized and underutilized land to finance urban infrastructure projects, including a 2012 committee report headed by former finance secretary Vijay Kelkar, many government departments have yet to take any significant action. The redevelopment of such government colonies, where at present officers enjoy lavish front yards while their neighbors in slums squeeze in nine to a room, must necessarily be advocated. While the abject obliteration of thousands of trees in one of the world’s most polluted cities should not ordinarily be the position of any responsible government official, the necessity for the densification of these holes in the fabric of the city is undeniable.

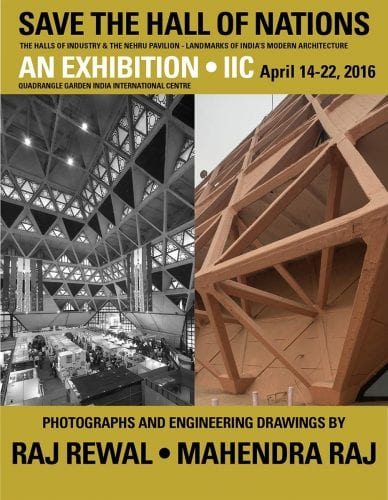

So what “wicked” solution may then be proposed? The current legal recourse of replanting ten times the number of trees felled is imprudent given the lack of oversight, the relocation areas being far from the original site, and the time that it takes for the environmental benefits of tree planting to be realized. Instead, we must first examine the process that necessitated this scale of green cover reduction. The National Buildings Construction Corporation (NBCC), the agency charged with the development, has a tarnished record of being heavy-handed rather than context specific in their projects. After their recent debacle of demolishing the Hall of Nations[3] – one of the gems of modernist Indian architecture – during the redevelopment of Pragati Maidan, it can safely be assumed that their approach would have started with the assumption of a clean slate for the design process. Instead, a Net Usable Land Area (NULA) analysis using a detailed mapping of the built and natural resources would have led to a more nuanced picture, which, though perhaps not as easily achieving as many housing units, would not necessitate such wanton destruction.

Next, to satisfy the density and land optimization requirements of polemical redevelopment projects, tools from other planning schema which allow a mediated path may be adopted. For example, Transit Oriented Development policies allow the capture of open and service areas by means of the Gross Floor Area Ratio to determine the permissible built-up area, instead of the Net Floor Area Ratios usually used in practice. This would allow a concentration of the developable areas away from the vulnerable green ones much in the same way that a Transfer of Development Rights does in the case of protected landmarks.

Finally, instead of looking to create private enclaves of manicured green for a select group of government residents, the vulnerable denser green pockets revealed by the NULA analysis should be envisioned as public green open space for the city. Much like Central Park in New York, these spaces would not only serve to mitigate the effects of high-density development, but also carve out recreation spaces for the general public. Being a part of the project area itself, transplantation of mature trees in close vicinity would have a significantly lower cost than to other distant locations. These public spaces within the project area can then be the site for any replanting still necessary due to local ordinances. By adding such public amenities, the course of stakeholder negotiations can be radically altered.

Thus, through first addressing the process and then reimagining the outcome, a balance can be achieved between opposing concerns while simultaneously creating leverage between disparate stakeholder groups. While this solution does not address the situation in totality, it changes the discussion from an either-or proposition to one with a more nuanced approach. Through this, it must always be kept in mind that, especially in dealing with complex concerns like public infrastructure, only “wicked” solutions are possible for such “wicked” problems. While there is no right answer, there is one that is net positive, and that is where successful practitioners must aim.

—

[1] Cantonments are permanent military garrisons in South Asia created by the colonial British now administered by the respective national Armed Forces according to the Cantonments Act of 1924. In addition to military bases, cantonments house civilian population but at a historically unchanged density, making them enclaves. In India, 200,000 acres of land (over 62 cantonments), an area larger than Mumbai and Kolkata combined, house only 5 million residents in comparison with the 17+ million residents of the two mega-cities.

[2] Rittel and Webber (1973) defined “wicked” problems that plague social affairs, unlike the “tame” problems that afflict design or science, as those with innumerable causes, without objective definition, and without an optimal answer (i.e. there are no “solutions” in the sense of definitive and objective answers).

[3] The Hall of Nations, designed by Architect Raj Rewal in 1972, was part of India’s post-colonial built heritage and one of the world’s only example of a large-span space frame structure built with concrete. However, it did not qualify as a heritage site under the government definition that stipulates a minimum age of 60-years and was demolished during the redevelopment of the area.

—

References

An exhibition of photographs and drawings by Raj Rewal and Mahendra Raj. (n.d.). Retrieved September 30, 2018, from Architexturez: In-Enaction: architexturez.net/pst/az-cf-177790-1460427334

Chapman Taylor. (n.d.). East Kidwai Nagar, New Delhi. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from Chapman Taylor Projects: www.chapmantaylor.com/projects/kidwai-nagar-east

Das Gupta, M. (2017, October 30). How much land does the Indian govt own? About 9 times the size of Delhi. Hindustan Times.

Mishra, L. (2018, January 27). India needs $330 billion to overcome housing shortage, says ANB Capital. The Hindu.

NBCC Ltd. (2017, March 27). World Trade Center, Nauroji Nagar. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from NBCC India Ltd. website: www.nbccindia.com

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973, June). Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Times News Network. (2018, June 24). Protests stepped up to save 16,500 trees in south Delhi. The Times of India.