Come 2019, millennials are projected to overtake baby boomers as the nation’s largest generation (Fry, 2018). It is imperative to understand how this shift will drive transformation of the built environment in the near future. Key among millennials preferences, is that of a live-work-play triad characterized as a flexible lifestyle that is experiential in nature with on-demand access to amenities. While these traits are typical of urban areas, suburbs still struggle with aligning to this new paradigm. As the next push of suburban development readies itself for the millennial generation, can urban ideals serve as a blueprint for future growth?

Being a part of an extended “Emerging Adulthood” phase, millennials are making very different choices than did past generations, particularly about housing. This includes when they leave home, where they choose to live, and the types of housing to which they aspire. Recognized for their low homeownership rates, millennials are typified

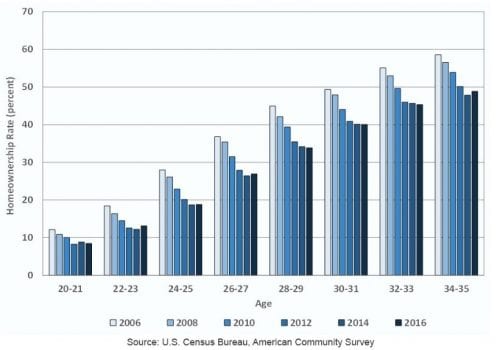

by their preference for either renting urban dwellings for short-term convenience (31%) or continued dependency on parents (65%) due to financial circumstances (CBRE, 2016), the latter brought on by an acute debt consciousness in the aftermath of the Great Recession and the ongoing Student Debt Crisis. While these may be the underlying factors, the de facto tipping point for homeownership has generally been starting a family which creates a need for the prolonged occupation for a larger space. Economically and spatially limited by options in the city, it triggers an exodus from the city in pursuit of larger, more affordable space.

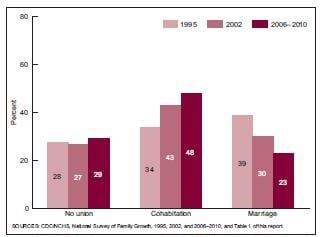

Examining the demographic drivers behind this delay, a large part can be attributed to a protracted period of singledom and the rising age of marriage among millennials in the quest for a more stable union (Cohen, 2018). While early marriage may have been put off, it has been replaced by cohabitation as a possible test of a relationship. This intermediate state is a likely motivation for flexibility in living arrangements.

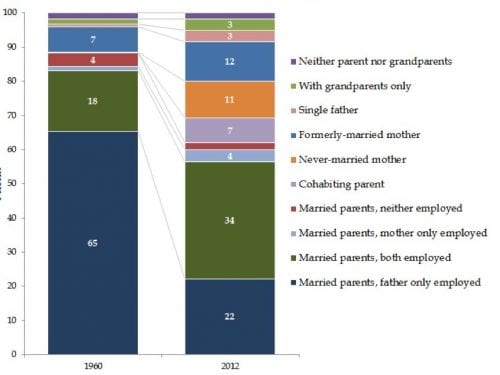

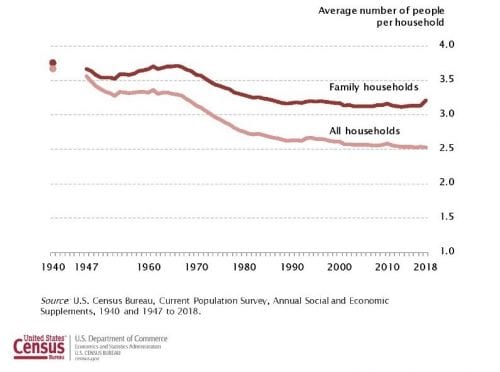

While marital status is a determining factor of the initial housing preferences of this generation, it also gives rise to a longer-term differentiation – that of family arrangements and household size. The rise in unintended births among cohabiting couples (Nugent & Daugherty, 2018) that may not ensue in marital union and a general acceptability of divorce has given rise to a vast diversity of family arrangements. This, coupled with delayed marriages and thereby reduced child-bearing potential post-marriage, has resulted in an average household size that has shrunk from 3.7 persons in the 1960s to 2.54 today (United States Census Bureau, 2018).

By 2016 though, as the earliest of the millennial generation crossed into their late 30s having married and started a family, a growing trend of homeownership was observed (Simmons & Myers, 2017). However, even in this choice there are distinct underlying variances between millennials and the generations before them that can reorient future development. The combination of smaller household sizes, lower levels of affordability, lower thresholds of debt, and a prior context of conceding space for convenience create a necessity for a denser living.

The growing trend of increasing suburban density through multifamily housing (Larco, 2014) is proof of this shift towards more compact living. In addition, with increasing flexible work options being offered by companies and growing numbers of independent workers, suburban co-working spaces are on the rise (Morris, 2017). Thus, with the first two spaces – live and work – being catered to, all that remains is the provision of recreation for these suburbs to function as semi-self-contained communities, mostly independent of the nearby city. The continuing failure of suburban malls presents an opportunity for the revitalization of suburbia by the creation of town centers through placemaking, whether through redevelopment, retrofitting, or even adaptive reuse. While 24-hour suburbia may be unviable, a relatively active 18-hour one would radically improve desirability. Among a generation of reduced car ownership and a greater dependence on transit and on-demand ride hailing, urbanization of the suburbs would need to go hand in hand with completion of the grid and improvement of walkability.

An examination of the opportunities in the suburbs directs attention to the dormant inner ring just outside the urban district that has generally not seen development activity since the initial suburban push. In addition to being accessible to the city through extended transit networks, these areas are seeing a rapid graying and eventual vacancy. While this offers a significant opportunity to bridge the housing gap and increase homeownership, there are initial hurdles that need to be overcome. Planning policy, government regulation and financial systems that affect suburban areas are overwhelmingly based on the single-family home and the nuclear family (Larco, 2010). Grayfield development has the added issue of land assemblage of subdivided plots to enable a holistic development pattern. Lastly, and probably most importantly, are the NIMBY powers who look at urbanization as an assault on existing ways of life.

The tide has begun to shift however, and despite teething issues, the rise of an urban-suburban seems to be an opportunity ripe for the taking. It would serve both developers and local governments to take cognizance of this fact and leverage it to revitalize large tracts of suburbia.

References

CBRE. (2016). Millennials: Myths and Realities. CBRE Global.

Cohen, P. (2018, September 15). The Coming Divorce Decline. doi:https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/h2sk6

Copen, C. E., Daniels, K., & Mosher, W. D. (April 4, 2013). First Premarital Cohabitation in the United States: 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Fry, R. (2018, March 1). Millennials projected to overtake Baby Boomers as America’s largest generation. Retrieved November 16, 2018, from Pew Research Center: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/03/01/millennials-overtake-baby-boomers/

Larco, N. (2010, Spring). Suburbia Shifted: Overlookied Trends and Opportunities in Suburban Multifamily Housing. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 69-87. doi:https://www.jstor.org/stable/43030893

Larco, N. (2014). Untapped Density: Site Design and the Proliferation of Multifamily Housing. Eugene: Sustainable Cities Initiative, University of Oregon.

Luscombe, B. (2014, September 4). There Is No Longer Any Such Thing as a Typical Family. Time. Retrieved November 18, 2018, from http://time.com/3265733/nuclear-family-typical-society-parents-children-households-philip-cohen/

Morris, K. (2017, June 18). Co-Working Spaces Spread to the Suburbs. The Wall Street Journal.

Myers, D., & Simmons, P. (2017, November 29). The Awakening of Millennial Homeownership Demand. Retrieved November 17, 2018, from Fannie Mae Perspectives: http://www.fanniemae.com/portal/research-insights/perspectives/millennial-homeownership-demand-myers-simmons-112917.html

Nugent, C. N., & Daugherty, J. (2018). A Demographic, Attitudinal, and Behavioral Profile of Cohabiting Adults in the United States, 2011–2015. National Health Statistics Reports, Center for Disease Control.

Parker, K., Horowitz, J. M., Brown, A., Fry, R., Cohn, D., & Igielnik, R. (2018, May 22). Demographic and economic trends in urban, suburban and rural communities. Retrieved November 15, 2018, from Pew Research Center Social & Demographic Trends: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/05/22/demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/

Simmons, P., & Myers, D. (2017, November 29). The Awakening of Millennial Homeownership Demand. Retrieved October 16, 2018, from Fannie Mae Research Insights: http://www.fanniemae.com/portal/research-insights/perspectives/millennial-homeownership-demand-myers-simmons-112917.html

United States Census Bureau. (2018, November 14). Historical Household Tables. Retrieved November 23, 2018, from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/families/households.html

Vespa, J. (2014, February 10). Marrying Older, But Sooner? Retrieved November 17, 2018, from United States Census Bureau Blog: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2014/02/marrying-older-but-sooner.html