The ubiquitous roadside motel – or at least the properties that host them – could find a new purpose in a starkly different America than the one in which they were conceived. Demographic shifts over the past several decades have made these properties largely irrelevant. The number of motels has declined from a peak of over 61,000 independent properties in 1964 to less than 16,000 in 2012 (Okrant, 2012). Unlike failing retail shopping malls of the same vintage, the programming and typology of these properties lends well to a number of potential new uses. With the right mix of circumstance and location, some of these motels may be ripe for redevelopment. Contemporary demand drivers like the pervasive lack of affordable, senior, and student housing may offer a creative solution for small-to-midsized developers scouring for deals in a tight real estate market.

The proliferation of Henry Ford’s automobiles coincided with the dearth of affordable, clean, and easily accessible accommodations. What could be called the first “motels” began to appear in the 1920’s, replacing more primitive auto camps or auto courts. America’s growing long-distance highway system, epitomized by the famous Route 66, caused these modest accommodations to spring up in pursuit of new transient visitors. The Dust Bowl of the 1930’s encouraged a mass westward migration of agricultural workers along Route 66 and other small highway systems, which necessitated evermore means of affordable and reliable accommodations (Margolies, 1995).

These “motor hotels” peaked in popularity in the early 1960’s, with familiar brands such as Best Western (1946), Holiday Inn (1952), Ramada (1954), and Motel 6 (1962) becoming some of the first franchise models. These brands, in addition to numerous independent operators, enjoyed quiet success as motel owners throughout the 50’s and 60’s. The emergence of freeways and the interstate highway system, however, led to more travelers bypassing the two-lane highways on which these independent operators found success. This massive shift in traffic patterns caused entire towns and economies to become obsolete. The larger chains were able to adapt their service models in order to accommodate the changing tastes and behaviors of American travelers. They also enjoyed capital reserves sufficient to abandon their obsolete properties and develop from the ground-up along new arterials and interchanges. New building typologies included more substantial accommodations and modern amenities, such as indoor pools, continental breakfast, full-service restaurants, and bell services. This continually shifting industry has generated thousands of underdeveloped and underperforming parcels in rural and suburban towns across the country.

At present, many of these blighted businesses are not worth the land they sit on. The typology and programming of these structures does not readily allow for conversion into the modern, limited-service offerings of competing companies such as EconoLodge, Comfort Inn, and Holiday Inn Express. However, due to continued urban sprawl and in-

fill development, these bypass corridors are once again becoming attractive markets. This attractiveness means these motels are typically demolished to allow for higher and better uses such as retail and office (Stevenson, 2017). Nevertheless, there remains a large stock of distressed motel properties scattered throughout the US that are not located in desirable urban growth or infill areas. Maturing franchises like Best Western and Days Inn took advantage of a mid-century influx of immigrants, particularly those from the Indian state of Gujarat, to expand into untapped markets. These newcomers were willing to relocate to rural areas in order to pursue a family enterprise, and to this day roughly half of the independently owned motels in the US are still run by families such as these (Starr, 2016). Changing tastes and upward mobility of such families has steered the second generation toward alternate career paths, and in many cases, this has led the aging ownership to begin dissolving their interests. Herein lies an opportunity for savvy developers to repurpose an American legacy while realizing significant value-added investments.

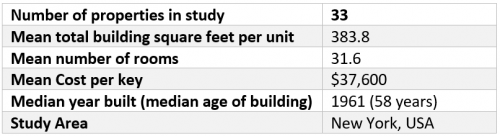

Revisiting this classic motel architecture, there are many noteworthy characteristics and features. For starters, a motel is typically a one or two-story structure, oriented with rooms facing a car-park, with no interior corridors. Guestroom entry doors are accessed from a covered balcony or patio directly adjacent to one or two dedicated parking spaces. Common areas and amenities are sparse, but all properties typically include laundry facilities, a check-in and reception area, vending machines, and perhaps a pool or playground, in addition to a dedicated property manager’s apartment and housekeeping rooms. A survey of over 30 currently listed pre-1975 independently operated motels indicates an average total square foot allocation on a per-room basis of 384 square feet and an average of 31.6 units.

One important idiosyncrasy of these buildings is the unit mix. A wide variety of accommodation types exist across the independently operated motels of this era. Unlike other short-term, select and limited service hotels and motels, which typically only offer a handful of room types, it is not unusual to find motels that offer rarities such as two-bedroom suites, detached cabins or cottages, or studio apartment style units complete with kitchenettes. These properties were not built with the same architectural efficiency available to larger chains and therefore often have a delightfully quirky layout.

Despite the sometimes-challenging architecture, a handful of adaptive reuse scenarios remain that might offer promising results. Renovating the average property from the survey above into modern hotel facilities can cost between a total of $276,000 and $646,000 (HVS, 2019), but existing floorplans translate well into other dwelling uses. Single room occupancy housing (SRO), for example, could make efficient use of private rooms with en suite bathrooms as a way to address local affordable housing deficiencies. Alternatively, areas with permissive zoning could allow existing suites with kitchenettes and bedrooms to be converted to rental housing. This would help alleviate regular vacancies. A property running at 60% occupancy, for example, might convert 40% of its rooms into rental housing by removing demising walls between adjacent units and converting one of the two bathrooms into a kitchen. In rare scenarios, an entire property could be converted into an assisted living facility or dormitory-style student housing.

Of course, as in the case of America’s dying retail malls, most suggested remedies can sound glib and overly optimistic. A developer hoping to repurpose a failing motel into a multi-family or co-living property will certainly face a challenging entitlement process. Motels, having gained a reputation for unsavory activity and blight, are typically zoned in commercial and industrial corridors where residential uses are expressly prohibited. Residential uses exist as-of-right or by a special use permit in only 5-10% of the areas where many of these motels are located. The potential for student housing and assisted care facilities can be, at best, a grey-area.

Financing of such redevelopment projects will also present a challenge. While shared accommodation student housing is well-established among university operators, privately managed co-living is a nascent trend which is only just beginning to gain credibility. Though likely an as-of-right use, assisted living facilities often require major retrofitting to accommodate ADA corridors, doorways, and rooms. In order for these deals to be acceptable to investors and banks, motels would have to satisfy a long list of criteria, including but not limited to flexible zoning and entitlements, purchase prices well below replacement costs, multiple reliable demand generators, and few major issues related to remediation or deferred maintenance (asbestos, mold, etcetera).

On the bright side, many of the aging motel properties available today would satisfy a significant portion of this list. Of the 33 motels evaluated, the purchase price was a mean 37.4% of replacement cost for limited service hotels of the same size (HVS, 2019). Moreover, the challenge of affordably housing the country’s rural working class has loosened the restrictive nature of zoning. Small sized developers might also qualify for various government-backed financing programs, such as the SBA’s 504 loan program. This program provides fully amortizing loans via a syndication between the SBA and a Community Development Corporation (CDC) for owner-occupied real estate investments up to $5 million. Moreover, motel conversions and/or renovations would almost certainly result in energy savings sufficient to qualify as “Green Energy” loans, meaning developers could finance multiple similar projects at one time under the program.

Combining government sponsored programs, demand for affordable housing in rural areas, and the community and political will to rehabilitate blighted commercial corridors is key to the preservation of this important piece of the American legacy. Small developers and investors who find themselves boxed-out of their local markets by increasing competition from larger firms stand to gain in these scenarios and small communities who found themselves stripped bare in the mid-century, brought on by the sea change of the interstate highway system, need not look farther than the humble motor hotel for a quick, creative fix.

Works Cited:

HVS, (2019). ’18/’19 Hotel Cost Estimating Guide. Rockville, MD: HVS Design Services.

Retrieved from: https://www.hospitalitynet.org/file/152004649.pdf

HVS, (19 September 2019). U.S. Hotel Development Cost Survey 2018/19. Westbury, NY: HVS.

Retrieved from: https://www.hvs.com/article/8597-us-hotel-development-cost-survey-201819

Okrant, M. (2012). No Vacancy: The Rise, Demise, and Reprise of America’s Motels. Bethlehem, NH: Wayfarer Press.

Margolies, J. (1995). Home Away from Home: Motels in America. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Co.

Starr, A. (5 March 2016). Here To Stay: How Indian-Born Innkeepers Revolutionized America’s Motels. NPR

Stevenson, J, (2017). Remembering the Alamo: Ways to Interpret What Remains of the Alamo Plaza Courts in a Present-Day Context. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.