Marinas, long the domain of local, independent owner-operators, have seen increasing interest from investors over the past 15 years. Now dominated by a few large institutionally backed firms, the industry has quickly transformed from one comprised of properties that store and service boats to one that has seen billions of dollars in capital inflows from firms seeking to capitalize on operational inefficiencies and a lack of historical investment. Combined with the steady cash flow generated by these businesses and high barriers to the construction of new supply, the nontraditional asset class has garnered a reputation as a serious opportunity for investment. But how has the industry changed, what are the main motivations of investors, and what does the future look like?

History of Marina Industry

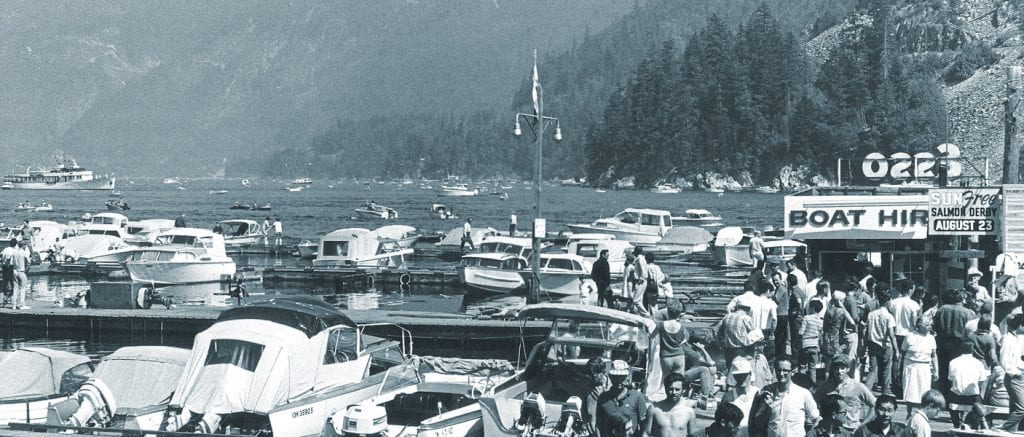

Although the concept of a marina arguably dates to the Roman Empire, the marina industry in the United States has developed gradually since the 19th century. After the passing of The River and Harbor Act of 1899, Congress gave the Army Corps of Engineers the authority to approve the construction of any structure on or over navigable waters1. Following a rise in consumer spending after World War II, recreational boating in the United States started to gain popularity, and like many other industries, thrived. This expansion led to further development of marinas – by 1960 there were 3,900 marinas and boatyards, 1,100 yacht clubs, and nearly 8 million recreational boats across the United States. Marinas have historically been local, family-owned operations. New federal regulations, such as the Water Pollution Control Act, Coastal Management Act, and the Clean Water Act of 1977, designed to protect the nation’s waterways against overdevelopment, pollution, and the destruction of coastal wetlands were at first difficult to interpret Coupled with double-digit inflation, high interest rates, and an oil embargo, it is surprising that the marina industry survived at all. Since the 1980s, however, the recreational boating industry has grown steadily. In 1990, about 8 million vessels were registered, rising to a peak before the Great Recession of close to 13 million vessels2.

What is a Marina?

Marinas provide docking, storage, and related supplies and services to recreational boat owners. Many sell fuel, provide repair services, and some even offer boat rentals. Marinas differ from ports in that they do not handle large passenger or cargo ships, although some do provide docking for yachts and mega yachts depending on size and access to deep water.

Approximately 70% of the marinas in the United States are private businesses, about 1-2% are private yacht clubs that only cater to their members, with the remaining 30% being owned and operated by local and state governments, typically at low or no cost to use1. The typical marina business model is to provide docking to both boat owners who rent a slip (dock space) or mooring (anchored space) monthly or for the season, as well as transient boaters who are looking to rent a slip or mooring for one or a few nights. Many marinas also provide dry rack storage, where specialized forklifts move boats from racks on the property into the water when owners want to use them, increasing the number of customers the marina can accommodate. Marinas take many shapes and sizes. There are some very large operations, such as Marina Del Rey and Dana Point in California that can accommodate thousands of boats, but the average size is 50 to 150 slips. One trend that emerged in the 1990s was the concept of “dockominiums” where the slips are treated like condominiums. Owners possess an interest in a certain slip on the dock, which can be sold, inherited, or transferred like any other interest in real property.

Marinas, like other hospitality sectors, are an operating business combined with the ownership of real estate. Like the operations of a marina, the real estate aspect can get complicated. Depending on the marina, an owner may have fee simple ownership of the ground underneath the water and docks while others may be subject to a sovereign or submerged land lease, with the lessor being a state agency or the federal government. Despite its challenges, investors have increased over the past decade seeking yield in a low-interest-rate environment, looking to take advantage of a fragmented industry that can benefit from economies of scale and operational efficiencies.

Institutionalization & the Current State of the Industry

A few key players, such as Safe Harbor Marinas and Suntex Investments, have led the push and attracted other well-capitalized investors into this niche space. A few key aspects of the marina business have attracted these investors and led to a transformation. Demographic trends, such as the “silver wave” of aging baby boomers, are one of the key drivers of this attention from institutional capital. Not only are many of the small-scale marinas owned by baby boomers, who may be looking to cash out and retire, but recreational boating has been proven to be a popular hobby in this demographic. As 10,000 baby boomers retire every day, boat sales and participation rates in recreational boating are being driven up. This has led to occupancy rates at marinas trending upwards from 2011 to 2018, with 70% of marina owners surveyed reporting occupancy over 95%3. Marina operators are looking to extend this growth to younger demographics through on-site boat rentals and access to memberships with companies like Freedom Boat Club, which provides members access to boats throughout the year, hoping that this will lead to these users eventually purchasing boats of their own.

Additionally, the competition for waterfront sites from residential developers in major coastal cities has led to the absorption of potential marina sites by developments with higher potential profitability such as waterfront condos, apartments, and hotels3. As these sites are absorbed, or worse, converted from marinas to other uses, the remaining boat owners suddenly have fewer spaces to store their boats. According to Baxter Underwood, CEO of Safe Harbor Marinas, “Theoretically to boaters, that’s a bad thing because there’s less slip space. For those left owning slips, it’s a great thing because there’s more demand for fewer slips. With regulations being what they are in the water around the country, I don’t see that changing.”4

These high barriers to new supply combined with the favorable demographic trends have positioned marinas as a compelling investment opportunity when pre-pandemic real estate prices for traditional asset classes were at historic highs.

Another aspect driving consolidation in the market is a classic private equity strategy – take a fragmented business with operational inefficiencies, build an operating platform that will allow a portfolio of assets to achieve economies of scale, then exit with a hefty profit having increased the efficiency and profitability of that business. These economies of scale are especially achievable on a regional basis, where companies such as Safe Harbor can employ managers with local knowledge, implement new business plans, and make capital improvements that the smaller owners may have neglected over time. The boom in marina transactions has not been exclusive to the coasts but has taken place across inland waterways as well. According to industry experts, the most attractive states have been those with the highest number of registered boats, both in saltwater and fresh – California, Florida, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin5.

Recent repositioning strategies include the concepts of branding and membership. Safe Harbor pioneered this model where a boater could have a membership with the company and as they travel from harbor to harbor and can stay at one of the company’s 100+ locations, expecting a certain level of service and amenities. Billed as the largest owner of marinas in the world, and with initial backing from the American Infrastructure Fund, Koch Real Estate, and Guggenheim Partners, Safe Harbor was recently acquired for over $2 billion by Sun Communities, a real estate investment trust traditionally focused on manufactured housing communities6.

Real Estate Around Marinas

Given the built-in foot traffic and activity around marinas, it makes sense that real estate developers would be drawn to them as investments. Across the country, developers have included marinas as part of large mixed-use development proposals. One such development, on Saco Island in Maine, seeks to turn a former industrial area close to Portland into a thriving mixed-use development with a marina, river walk, residential units, commercial space, a hotel, and open space for the public to enjoy. Despite traffic concerns, the community is excited at the potential for increased activity in this underdeveloped area, anchored by a new marina. Craig Pendleton, the executive director of the Saco Chamber of Commerce, shared his thoughts on the project, from his point of view as chamber director and his background as a fisherman. “I’m excited we could potentially have another marina down here. I imagine whale-watching boats and dinner cruises on the river, he said. All that potential is just waiting to happen.”7

It’s not just coastal resort destinations and underdeveloped towns in New England where new marinas are being constructed. Touted as New York City’s first new marina in 50 years, OneO15 Brooklyn Marina opened to the public in 2016. Developed by Singapore-based SUTL Enterprise, which specializes in marina development, the $28 million project on eight acres includes 102 slips, alongside a community boating program for free and low-cost boating.8

What does the future hold?

When looking towards the future of the marina industry, the demand and supply metrics certainly bode well for continued investment. One trend that is here to stay is interest from institutional investors looking to unlock value by upgrading marinas into destinations surrounded by amenities and leveraging their brands to establish brand loyalty. According to a market outlook by Marcus & Millichap, investments in dock upgrades, the addition of restaurants, boutique hotels, and even boat rentals will be additions that marina owners looking to create value can implement. Well-located marinas with development potential will particularly attract attention from investors looking to develop mixed-use, residential, and hotel properties with built-in demand drivers. One such example, the Hilton Fort Lauderdale Marina, traded for over $170 million in 2018. Demonstrating that it’s not just pure marina investors targeting the asset class, the buyer was an affiliate of Brookfield Asset Management and the seller was an affiliate of Blackstone, two of the largest real estate owners in the world. Granted, the property includes a 589-room hotel with event space in addition to its 33-slip marina, but according to Paul Weimer, SVP at CBRE Hotels, the potential for redevelopment on the nine-acre property was the key motivation of the transaction. “With tremendous potential for future redevelopment, this truly unique investment allows ownership to acquire fee-simple, waterfront real estate in a destination where demand continues to grow,” he noted at the time of the sale9.

In locations where water frontage is limited, look for marinas to continue investments in dry storage. Automation is a relatively new trend in the dry storage space that industry experts see as a way to negate the dearth of space available for storing the growing number of boats in the water. Unlike forklifts, which are limited in how high they can lift boats, automated systems which use an internal crane system can retrieve, maneuver, and store boats in much less square footage. While a forklift system is limited to three to five racks in height, automated systems can store and retrieve on racks over 100 feet high on a narrower footprint. Like more traditional asset classes of real estate, this increased density and income per square foot is a promising solution for marina owners looking to maximize profit. Given the emphasis put on efficiency by traditional private equity investors, this will be a popular upgrade to marinas where dry dock storage is already in use, or where there is adjacent land available, especially when compared to the difficulty and cost of installing new docks.10

In the world of real estate, marinas are one of the more unique asset classes. Combining an operationally intensive, hospitality-style business model with waterfront property and the restrictions and limitations that these locations can bring requires creative ownership to maximize value. Therefore, it is not surprising that institutional capital has entered and dominated this space as investors look to seize the opportunity in a fragmented and traditionally inefficient industry. When combined with the potential to develop waterfront property alongside marinas, using the business as both an amenity and a demand driver, the attractiveness is intensified, and the pool of potential investors is widened to include more traditional real estate investors and developers. As the number of opportunities dries up, new technology such as automated dry dock storage will prove integral to maximizing efficiency and therefore the value created on ever smaller plots of land.

References

-

Encyclopedia of Business, 2nd ed. SIC 4493 Marinas. Reference for Business. (n.d.). https://www.referenceforbusiness.com/industries/Transportation-Communications-Utilities/Marinas.html.

-

Lange, D. (2020, December 3). Recreational Boating – Statistics & Facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/1138/recreational-boating/.

-

Leisure Investment Properties Group/Marcus & Millichap. (2020, January). Leisure Investment Properties Group: 2020 National Marina Market Investment Report. https://www.leisurepropertiesgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2020-Marina-Investment-Report.pdf.

-

Haynes, R. (2017, November 20). Seeking treasure at marinas. Trade Only Today. https://www.tradeonlytoday.com/dealers/seeking-treasure-at-marinas.

-

Trends Report: A Decade of Marina and Boatyard Industry Data. Marina Dock Age. (2020, March 3). https://www.marinadockage.com/trends-report/.

-

Marinas, S. H. (2020, September 29). Safe Harbor Marinas Announces Merger Agreement With Sun Communities, Inc. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/safe-harbor-marinas-announces-merger-agreement-with-sun-communities-inc-301140059.html.

-

Saco island targeted for $40 million development. (2017, Jul 25). Real Estate Monitor Worldwide Retrieved from https://www-proquest-com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/wire-feeds/saco-island-targeted-40-million-development/docview/1922874083/se-2?accountid=10267

-

ABOUT ONE°15 Brooklyn Marina. One15 Brooklyn Marina. (n.d.). https://one15brooklynmarina.com/about-one15-brooklyn-marina/.

-

Cohen, D. (2018, June 20). CBRE Brokers $170.6M Sale of Hilton Fort Lauderdale Marina. REBusinessOnline. https://rebusinessonline.com/cbre-brokers-170-6m-sale-of-hilton-fort-lauderdale-marina/.

-

Weykamp, G. (2018, April 6). Automated Dry Storage Marinas Provide Solutions to Many Waterfront Challenges. Marina Dock Age. https://www.marinadockage.com/automated-dry-storage-marinas-provide-solutions-many-waterfront-challenges/.