Introduction

Fig 1. Rendering of “The #Unignorable Tower.” Photo Credit: United Way Greater Toronto & Norm Li (Li, 2019)

As it rises to become a formidable economy, Toronto faces a crucial time in its history. The problems of housing shortage and affordability have persisted in the past, but are now even more prevalent as the city continues its rapid expansion. In an effort to demonstrate the immediate need for affordable housing, United Way Greater Toronto has created a campaign through “The #Unignorable Tower”, a powerful image representing the magnitude of low-income families across the Greater Toronto Area struggling to afford housing.

There are three main indicators that reveal the economic and demographic growth of Toronto. First, the Greater Toronto Area experienced a 4.8% increase in employment from the third quarter of 2018 to the third quarter of 2019 (Ontario, n.d.). Second, Toronto’s GDP grew by 3.3% in 2017 (City of Toronto, n.d.). Third, between July 2017 and July 2018, Toronto saw a net in-migration of 77,435 into the city, which was the highest in North America, with the next highest being 25,288 in Phoenix AZ (Clayton & Shi, 2019). While all these factors point towards a strong economy, under the surface, a very tight rental market is being stretched even thinner.

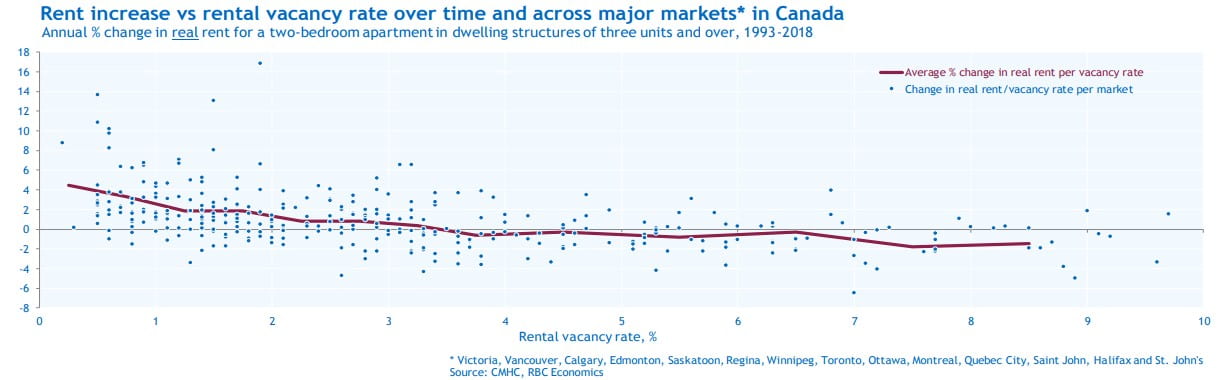

Fig. 2 Stabilizing Vacancy Rate. Credit: RBC Economics (Hogue, 2019)

A study of various rental markets across Canada shows that a general vacancy rate of 3% tends to indicate a stable rental market. This ideal scenario is when there is neither upward nor downward pressure on real rents because nominal rents rise only with inflation. Upward pressure on rent prices intensifies when rental vacancies drop below 3% as seen in Figure 1. Currently, Toronto’s vacancy rate is at 1.1%, and the same study shows that 9,100 new rental units had to be supplied in 2019 alone to drive vacancies up to the stabilized level of 3% (Hogue, 2019).

An increased barrier to homeownership has also put upward pressure on the rental market. In 2018, Canada introduced the “mortgage stress test” that imposed stricter qualification requirements on a potential borrower, in the event interest rates rise. This test came about to tackle the high debt most Canadians have incurred. The new requirement has successfully slowed down mortgage lending by about 7%, and reduced the purchasing power of a potential homebuyer by about 20%, effectively cooling the housing market (Sokic, 2019). When faced with obstacles to homeownership, people often turn to the rental market for a place to live, hence driving up rental demand.

Toronto’s Rental Market

Toronto’s rental market is split into two categories. The primary market comprises purpose-built rentals, commonly known as multi-family or multi-residential apartments. These buildings are developed and managed by real estate companies. The apartment units are not for sale, but intended to be fully rented out. On the other hand, the secondary market is where condominium units, or individually-owned homes, are rented out. The availability of these units on the rental market is highly unpredictable. As the category names suggest, the primary market is expected to provide most of the relief in rental shortages in Toronto, but in actuality, the city relies heavily on the secondary market. The problem extends even deeper. In the first three quarters of 2018, there were only 3,000 rental unit construction starts, compared to 19,500 condo unit construction starts (CMHC, 2018).

Relying on the secondary market can present two problems. First, it opens the possibility of rent discrimination, where certain demographics might find it harder to rent depending on the landlord’s preference for tenants. Second, and more importantly, the secondary rental units are not a reliable long-term solution. Investors in condo units might put their space on the rental market for a year or two as they transition to move in, or they might keep it vacant to preserve it for a future inheritance, or simply for capital appreciation.

Indeed, the city has floated the idea of a “Vacancy Tax” as a way of forcing the vacant condo units back on to the market. In addition to providing relief in the supply market, any funds generated through this tax can be put towards incentives for encouraging even more affordable housing. Vancouver, another tight housing market, introduced a similar “Empty Homes Tax” in 2016, and raised $38 million in it’s first year (CBC News, 2019).

Although it can be difficult to prove whether a condo unit is vacant, photographer Jaco Joubert recently came up with a creative way to estimate vacant condo units. Joubert, using only a camera, documented how consistently lights were turned on in each unit over a week, and then overlaid all the photos and converted them into a heatmap to manually count the vacant units using floor plans of each condo. He studied 15 condos, and found approximately 5.6% of the units uninhabited. Extrapolating this rate across the entire condo stock in Toronto, combined with the average new condo unit construction starts, the result suggests that approximately two years’ worth of new condo supply sit vacant and off the rental market (Joubert, 2019).

Fig. 3 Heatmap of Overlaid Photos Showing Typical Vacancy in a Condo. Photo Credit: Jaco Joubert (Joubert, 2019)

Recent History of Rental Apartments in Toronto

To fight the tendency for new housing stock to sit vacant and off-market, the discussion for rental supply needs to turn back to the primary market. Unlike individual condo owners, rental apartment owners have every intention of fully leasing-up their apartment buildings.

The current “Residential Tenancies Act”, which governs all landlord and tenant relations, was created in 2007. Initially, under this act, any building constructed prior to November 1, 1991, was subjected to rent control provisions, which caps annual rent increases at the previous year’s CPI, or 2.5% (whichever is lower). In 2017, former Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne announced the “Fair Housing Plan,” which stretched rent control provisions across the entire rental market. Finally, on November 15, 2018, the current Premier Doug Ford enacted new legislation releasing any new residential construction from these rent control provisions.

So just how effective is rent control? The RBC report shows that in 2018, rent prices in Toronto still increased by 4.5% and 4.0% for rental apartments and condo units respectively (Hogue, 2019). This is because rent control only applies to existing tenants looking to renew their leases. When a unit turns over to the rental pool, rent is bumped back up to market rate, or maybe even higher to compensate for the restrictions. A 4.0% annual market rent increase far exceeds the 2.5% rent control guideline set out by Ontario’s Residential Tenancies Act. By means of comparison, The Brookings Institution reported that in San Francisco in the 1980’s, rent-controlled apartments were 8% more likely to convert to a condo, which attracted residents with 18% higher income, and contributed to gentrification, the opposite of what rent regulation intended to achieve. The report also found that rent-controlled buildings are less likely to invest in maintenance and building improvements, leading to building decay (Diamond, 2018). And capping rental revenue growth can sometimes easily kill the deal for rental apartment developers. In essence, rent control laws can sometimes do more harm than good for the rental apartment industry, which arguably has the highest potential to provide relief in the rental market.

Barriers to Rental Developments

In addition to rent control, there are other factors to consider when evaluating the feasibility of an apartment development, says Faraz Hirji, Director of Development Finance at Dream Unlimited. Dream Unlimited is a real estate company that in the past has been involved with many successful condo developments, but recently has shifted their strategy to include long-term assets such as rental apartments.

One of the fundamental differences between developing a rental and a condo lies in the outcome after construction is complete. When a rental apartment is built, the developer will generally hold the asset long-term and rely on its annual income, or find a buyer to take over the building. Alternatively, once a condo is built, the developer receives all closing proceeds from the condo unit sales, pays off any construction debt, repays equity and profits, exits the deal, and moves on to the next development.

As part of the condo pre-sales, the buyer typically puts down about 15-20% of the sale price as a deposit, and altogether these collected funds contribute to the capital stack required to start the condo development project. This is important because it lowers the equity needed by the developer and its investors, resulting in an even higher leveraged IRR. Additionally, traditional construction loan financing rates are more favorable to condos because their projects are backed by pre-development sale commitments. On the other hand, it is very difficult for a rental project to secure pre-development leasing commitments from residential tenants before an apartment complex is built. Without a stabilized occupancy and income level, lenders would have to charge a higher interest rate to account for the additional risk on the loan. Since developers also exit as soon as the condo reaches occupancy, they do not assume the risk of holding the asset in a weakening rental market, or the political risk from unexpected changes in rent regulations.

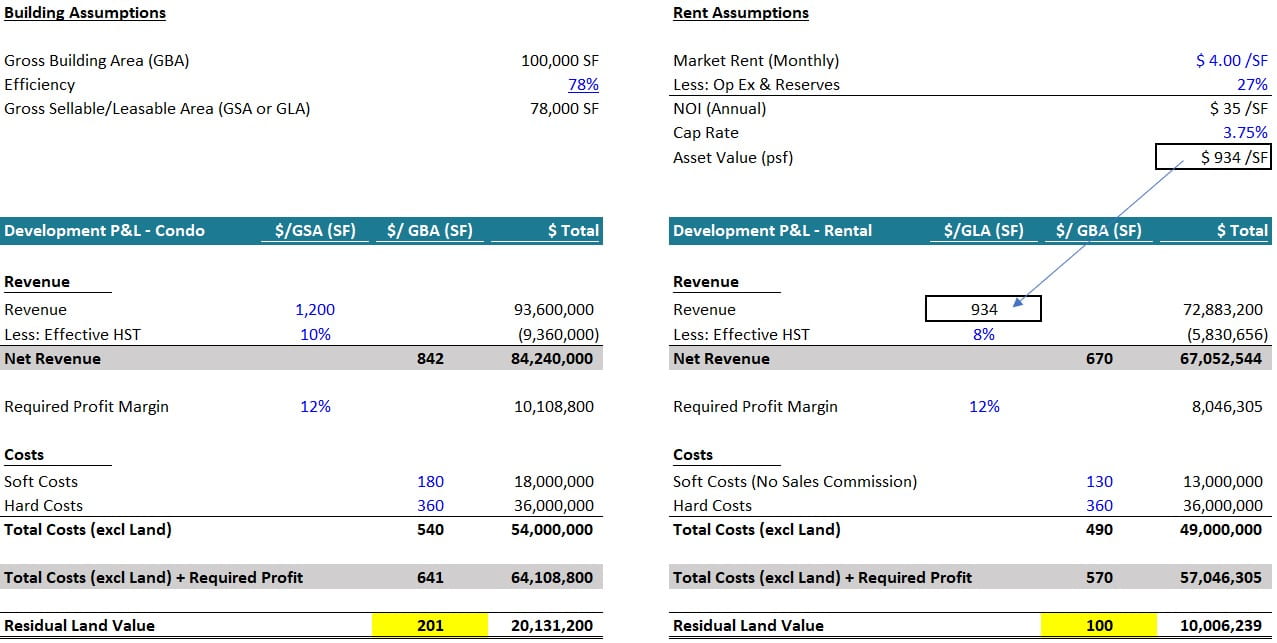

Finally, there is also the consideration of bidding for land. When a site goes up for sale, and if a condo development and a rental apartment development compete for the same site, the following residual land value calculation demonstrates the difference in purchasing power for land. The assumptions used below are prevailing market conditions in downtown Toronto at the time of writing. Even though both condo prices and market rents have been on the rise in recent years, simply because condos now sell for around $1,200/SF, the condo project has the ability to outbid a rental apartment proposal by twice the amount for land ($200/GSF vs. $100/GSF).

Fig. 4 Residual Land Value Sample Calculation

The Government-Owned Surplus Land

If it comes down to the purchasing power for land that prevents a rental development deal from penciling, then what other options do developers have? The answer might lie in the surplus land that the Federal, Provincial, and Municipal government have in stock. Surplus land refers to a site that is either vacant or underutilized based on its potential to increase density (Petramala & Amborski, 2019). A classic example of surplus land would be a surface parking lot surrounded by adjacent skyscrapers in an urban area. A recent Ryerson University report points to a large inventory of government-owned surplus land that can be effectively used to provide more affordable housing either by selling the land below market value, or by leasing the land. In both options, in exchange for lowered land costs, the developer has to agree to provide some portion of affordable housing in their development (Petramala & Amborski, 2019).

Several ideas have been launched to use surplus land for affordable housing. One of them is The Housing Now initiative, which invests city-owned land into the development of mixed-used, affordable, transit-oriented communities. However, it was the Infrastructure Ontario’s Provincial Affordable Housing Lands Program (PAHLP) that truly allowed Dream Unlimited and it’s investment partners to overcome the land-cost barrier, and brought to fruition a purpose-built rental development. As part of the PAHLP, Dream holds a 99-year land lease on a site at the West Don Lands by Toronto’s waterfront. The project will supply 761 rental units to the market, of which 229 will be affordable units that can provide rents as low as 40% of average market rent (CMHC, 2019).

Fig. 5 View of proposed rental apartment at West Don Lands. Photo Credit: Dream Unlimited (White, 2019)

Instead of the heavy upfront investment in land for a rental development, the cost of land is now just another annual operating expense. Faraz Hirji says that such government initiatives can really unlock the value of the land, not just from a developer’s perspective, but also from the city’s. Prior to leasing this land, the site was used for surface parking. Leasehold structures also ensure that the government maintains ownership of the land, which give them the ability to mandate certain clauses as part of the lease agreement. This might include requirements of having a certain percentage of affordable units at a certain percentage of Average Market Rent (AMR).

The Canadian Mortgage Housing Corporation Rental Construction Financing initiative (CMHC RCFi) is yet another vehicle that encourages rental apartment developments. Currently, this program offers funds up to $13.75 billion, aimed at supplying 42,500 new rental units. Under the RCFi, developers can borrow up to 100% Loan-to-Cost (LTC), and amortize the loan over 50 years, both of which lower the risks and raises the returns for the borrower, ultimately bringing a rental development deal closer to competing with a condo proposal. In order to qualify for this loan, the project needs to be a rental property with a minimum of 20% affordable units, and prove that their potential rental income is 10% below achievable levels supported by an appraisal (CMHC, 2018).

Conclusion

As residential vacancy rates in Toronto hover around 1%, there has never been a better time for the public and private sector to be investing in rental apartments. Fundamentally, it has been a resilient asset class as even in a down-cycle, rent prices may fall, and vacancies might jump, but city residents will always need a place to live, and so strong rental demand will continue to favor apartment assets as part of a long-term strategy. With initiatives such as leasing government surplus land, and providing favorable rental construction loans, the Toronto residential rental industry is finally taking steps in the right direction.

References

CBC News. (2019, November 12). Councillor calls on city to mull vacancy tax after man does own study of empty condos. Retrieved from CBC: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/councillor-ana-bailao-vacancy-tax-jaco-joubert-condo-tower-study-1.5357198

City of Toronto. (n.d.). 2018 Issue Briefing: Toronto’s Economy. Retrieved from Toronto: https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/council/2018-council-issue-notes/torontos-economy/strengthening-torontos-economy/

Clayton, F., & Shi, H. (2019, May 31). WOW! Toronto Was the Second Fastest Growing Metropolitan Area and the Top Growing City in All of the United States and Canada. Retrieved from Center for Urban Research and Land Development: https://www.ryerson.ca/cur/Blog/blogentry35/

CMHC. (2018, May 2). National Housing Strategy: Rental Construction Financing. Retrieved from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/nhs/rental-construction-financing-initiative

CMHC. (2018). Rental Market Report: Greater Toronto Area. Retrieved from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: https://eppdscrmssa01.blob.core.windows.net/cmhcprodcontainer/sf/project/cmhc/pubsandreports/rental-market-reports-major-centres/2018/rental-market-reports-toronto-64459-2018-a01-en.pdf?sv=2018-03-28&ss=b&srt=sco&sp=r&se=2021-05-07T03:55:04Z&st=2019-05-06

CMHC. (2019, June 27). Making Housing More Affordable for Middle-Class Families in Toronto. Retrieved from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/media-newsroom/news-releases/2019/making-housing-more-affordable-for-middle-class-families-toronto

Diamond, R. (2018, October 18). What does economic evidence tell us about the effects of rent control? Retrieved from The Brookings Institution: https://www.brookings.edu/research/what-does-economic-evidence-tell-us-about-the-effects-of-rent-control/

Hogue, R. (2019, September 25). Big City Rental Blues: A Look at Canada’s Rental Housing Deficit. Retrieved from RBC Economics: Focus on Canadian Housing: http://www.rbc.com/economics/economic-reports/pdf/canadian-housing/housing_rental_sep2019.pdf

Joubert, J. (2019, November 6). Are Condo Units Really Sitting Empty in Toronto? Retrieved from move smartly: https://www.movesmartly.com/articles/condo-units-sitting-empty-in-toronto

Li, N. (2019). #Unignorable. Retrieved from Norm Li: https://normli.global/portfolio/unignorable/#

Ontario. (n.d.). Ontario Employment Report. Retrieved from Ministry of Economic Development: https://www.ontario.ca/document/ontario-employment-reports/july-september-2019#section-3

Petramala, D., & Amborski, D. (2019, April 29). Governments in Ontario Making Headway in Using Surplus Lands for Housing. Retrieved from Ryerson University, Centre for Urban Research & Land Development: https://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/cur/pdfs/CUR_Report_Surplus_Lands_April_29.pdf

Sokic, N. (2019, November 7). Why the mortgage stress test has proved so controversial for first-time homebuyers — and retirees. Retrieved from Financial Post: https://business.financialpost.com/real-estate/mortgages/mortgage-stress-test-first-time-homebuyers-and-retirees

White, C. (2019, June 27). West Don Lands Affordable Housing Gets Funding. Retrieved from Urban Toronto: https://urbantoronto.ca/news/2019/06/west-don-lands-affordable-housing-project-gets-funding